War kills people and destroys human creation; but as though mocking war’s devastation, flowers inevitably bloom through its ruins. After a long siege, a prolonged bombardment for months from all around the harbor, and numerous fires, the beautiful port city of Charleston, South Carolina, where the war had begun in April, 1861, lay in ruin by the spring of 1865. The city was largely abandoned by white residents by late February. Among the first troops to enter and march up Meeting Street singing liberation songs was the Twenty First U. S. Colored Infantry; their commander accepted the formal surrender of the city.

Thousands of black Charlestonians, most former slaves, remained in the city and conducted a series of commemorations to declare their sense of the meaning of the war. The largest of these events, and unknown until some extraordinary luck in my recent research, took place on May 1, 1865. During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the planters’ horse track, the Washington Race Course and Jockey Club, into an outdoor prison. Union soldiers were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of exposure and disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand. Some twenty-eight black workmen went to the site, re-buried the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

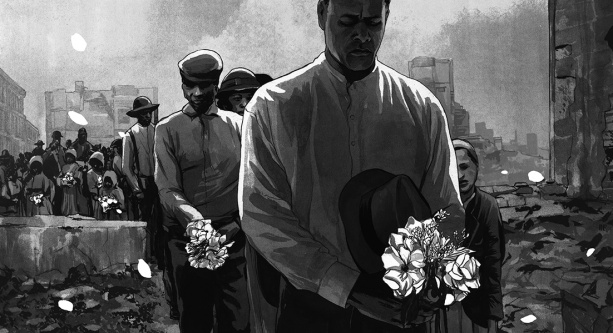

Then, black Charlestonians in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged an unforgettable parade of 10,000 people on the slaveholders’ race course. The symbolic power of the low-country planter aristocracy’s horse track (where they had displayed their wealth, leisure, and influence) was not lost on the freedpeople. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

At 9 a.m. on May 1, the procession stepped off led by three thousand black schoolchildren carrying arm loads of roses and singing “John Brown’s Body.” The children were followed by several hundred black women with baskets of flowers, wreaths and crosses. Then came black men marching in cadence, followed by contingents of Union infantry and other black and white citizens. As many as possible gathering in the cemetery enclosure; a childrens’ choir sang “We’ll Rally around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and several spirituals before several black ministers read from scripture. No record survives of which biblical passages rung out in the warm spring air, but the spirit of Leviticus 25 was surely present at those burial rites: “for it is the jubilee; it shall be holy unto you… in the year of this jubilee he shall return every man unto his own possession.”

I encourage you to read the entire article documenting the history behind Memorial Day.

Today’s post is to honor the freedom fighters and soldiers of the Flowers family. Beginning with the children’s father, who I can rightfully say, was among the black soldiers and civilians who initiated Decoration Day, known now as Memorial Day.

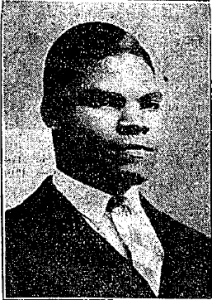

Harry Flowers

“I am 43 years old, a carpenter, residence and P.O. Address is at Mandarin, Duval County, Fla. I was 5th duty Sergt. of Co. A 21 Regt U.S.C.T. and served from the fall of 1865 [sic] to until the M.O. [muster out] of our Co. April 25/66. I first knew the dec’d, husband of cl’t in the service, when we got to Hilton Head S.C. I enlisted at Jacksonville, Fla…”

Harry F. Flowers, January 7, 1891

On July 17, 1864 in Jacksonville, Florida, former enslaved and free blacks stood in the Union army’s enlistment line. Waiting, was a young black male standing at a mere five feet and four inches. He was a former slave from Putnam County, Florida.[2] As Lieutenant George F. Hopper asked the young man for his name he replied Harry Florence Flowers. Harry was assigned to Company A and F of the 21st United States Colored Infantry (USCI), a garrison and fatigue unit composed of former slaves from South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. He was faced with his fair share of discrimination given lower wages than white soldiers and handed the shovel more times than weapons of war. Although there would be no film showing their glory, one of the 21st USCI’s greatest achievements is being recognized as the first Union army to enter Charleston after the city’s surrender in 1865.

Chauncey Flowers

Employed as a bartender and waiter in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Chauncey’s life shifted gears as the United States became involved in the First World War. At the age of 22, he was enlisted into the 351st Heavy Field Artillery regiment of the 92nd Division of the army, an exclusively African American division.He trained at Camp George G. Meade, Maryland.

The 351st Field Art. Regiment was under the command of Colonel William E. Cole, Lieutenant Colonel Edward L. Carpenter, Major Eric Briscoe, and Major Wade H. Carpenter.[4] The 351st are remembered for conducting themselves with fortitude and valor during the last battle of World War I fighting with great precision and order.[5] The mayor of Pittsburgh praised the works of these men proclaiming,

On Friday morning of this week Pittsburgh will have the privilege of welcoming home from overseas a part of the 351st Field Artillery Regiment, composed of colored troops…When President Wilson issued his appeal, calling upon the people in these United States to rally to the support of ‘Old Glory’ there was a noble response. None was more spontaneous than that from the colored people of this nation. By their deeds they have written their names in golden letters in history….Those who bore arms for us were first in war. In peace let us show them that they are still first in the hearts of their fellow-citizens.

Vincent Flowers

On May 26, 1942, Vincent was drafted into the Second World War. Little remains known about his war; however, it is known that he was stationed in the South Pacific for three years.

Although the Flowers women were unable to participate in the war abroad, they were fully involved in the war here in at home in America. Freedom fighters in Philadephia, New York, Mississippi, and Georgia, the Flowers women did not remain silent to the injustices against blacks in America. Because of their efforts and accomplishments, I must give honor where honor is due.

Rachel Flowers

“What profession is there today that the Negro is not capable of filling? He [She] is optimistic, race conscious, and desires the rights and privileges granted to other Americans.”

Rachel was a trailblazer. In 1916, she became the first African American to enroll at Messiah Bible School and Missionary Training Home located in Grantham, Pennsylvania. Today this school is known as Messiah College, my alma mater. While keeping her father’s home outside of Boiling Springs, Rachel and most of the Flowers family migrated to Philadelphia. The rising black population in the city led to even social and legal segregation, issues that originally caused blacks to flee the South. Rachel turned to the cornerstone of the black community, the black newspaper, to voice her anger against this systematic racism and oppression. On October 8, 1931, the Tribune published Rachel’s letter to the editor entitled “What Have You to Say?: A System that Breeds Prejudice”. In this article, she challenges the Board of Education to reconsider their acceptance of the theory that the black teacher’s proper place is found in black schools.[12] She argues,

On the contrary, the best interest of the American children is served under the efficient teacher, irrespective of race or color. The Negro teacher will then be given the proper place. The competent Negro will be appointed to teach, not only in colored schools, but in mixed, junior, and senior high schools and colleges in Philadelphia and elsewhere. The poisonous venom of prejudice is largely practiced in schools. Hence, if we will oust segregation from the school system, segregation as a whole is doomed.

This would only be the beginning of her involvement in the community. Between the 1930s to the 1960s, numerous political, fraternal, medical, educational, and cultural organizations arose from Philadelphia’s black community.

Hilda Flowers

In 1964, Hilda became involved with the Civil Rights Movement and grassroots organizations established during the 1960s. She was asked by members of the community to work as the administrative secretary of the Philadelphia chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC. Through her work with SNCC, Hilda was responsible for supervising the office and organizing volunteers. She coordinated fundraising events, maintained the speakers’ database, and served as the spokesperson of Philadelphia’s SNCC speaking at colleges, churches, homes, and local gatherings. After a year in service with SNCC, Hilda took on a new position with the Philadelphia Tutorial Project (PTP) directed by David Hornbeck. She worked for the PTP until 1966 when she found her new calling in Mississippi.

Not a stranger to the Mississippi Delta, Hilda traveled to the area through her work with SNCC. As she relocated to Mississippi, she was employed as a staff member for the Poor People’s Corporation (PPC). Her work is noted in Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Trailblazers and Torchbearers, 1941-1965. After briefly returning to Philadelphia in 1967, she returned permanently to Jackson, Mississippi continuing her work with PPC until she joined Friends of the Children of Mississippi (FCM) in 1968. Invited to join the advisory board of the Mississippi Institute of Early Childhood, Hilda served as a member until her death in 1975. She also served as a broad member of Operation Shoe String and president of the Business and Women’s Professional Club of Jackson.

Her daughter, Geraldine Wilson, writes in her mother’s biography,

She will be remembered for her strength, her humor, her determination, her honesty, her warmth, her supportiveness, and her sense of justice. She is survived by two sisters, Racheal [sic] and Gladys; by two brothers, John and Vincent; by her children, Gerry, Herb, and Harry; and her grandchild, Nandi; and nieces, nephews, and close friends who will miss her. We, her family, are proud to leave her “home” with all of you. You have taken fine care of her for us these last eight years. You have our gratitude and our love. May her life be an example for us all.

Geraldine Wilson

Launched by the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer Project involved more than 1,000 volunteers journeying South for civil rights. Geraldine traveled alongside these volunteers to Jackson, Mississippi and Albany, Georgia. She remembered the “palpable fear of travelling the back roads of Mississippi at a time when Civil Rights workers were being beaten and killed, or the bravery and quiet heroism of the workers and citizens who supported the Movement at great personal risk”. She launched training sessions designed to teach strengthen the city’s black community and seminars for teachers within the Head Start Programs. Regardless her work in Philadelphia or SNCC, education always remained her true passion.

Geraldine went on to complete her Masters’ in Group Dynamics and Human Relations and worked towards a doctorate in early childhood education until her death. In 1973, while working as an instructor of early childhood education at Teachers College, Columbia University, and the New School for Social research, she accepted the position of Director of Regional Training at Head Start Programs in New York City. Her work extended to the Child Development Group of Mississippi, Friend of the Children of Mississippi, the Queens College of New York, the Head Start Program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Battle Creek, Michigan, the Philadelphia Board of Education, the United Community Corporation of Newark, New Jersey, the Mary Holmes College and Field Foundation, the staff of the Newark Diocese Summer Program, the Ossining School Board in New York, and the Teaneck School Board of New Jersey. In 1979, she was hired as a full-time consultant with her of list of clients including national children’s organizations, corporations, universities, and school systems. She rose to become a widely respected, published, and prominent speaker.

Happy Late Memorials Day!

Until the next post,

Christina

Leave a comment