“People feared the Klan…until the Klan picked a fight with people who fought back.”

Now, before I write present the Battle of Hayes Pond, I must first inform you about the history of Maxton, North Carolina and the Lumbee Tribe. Both hold a special place in my heart.

Spending pieces of my childhood in Maxton, North Carolina, there were some advantages and some disadvantages to living in a small town. The town only consist of three stop lights, perhaps four now, two grocery stores, one being a Piggly Wiggly, and a Family Dollar. Fried chicken may be purchased from the local gas station and Main Street is the only street as far as I am concerned. You can walk on the road, stay outside in silence, and go on long adventures. On the other hand, boredom hangs over the city like a fog, everyone knows when you did something wrong, and the nearest mall is about an hour away. I spent my preschool years at R.B. Dean Elementary School, the only town’s only elementary school, and graduated from the 8th grade at Townsend Middle School, the town’s only middle school.

Maxton is approximately 2.2 square miles. This area was first “settled” by Scottish immigrants in the 1700s; however, this region was originally inhabited by several tribes including the Chowanoke, Roanoke, Pamlico, Machapunga, Coree, Cape Fear Indians, Meherrin, Cherokee, Tuscarora, and the Siouan tribes. In 1885, the tribe which continued to live throughout the southeastern region of the state were recognized as the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. Named after the Lumber River that runs throughout Robeson County, there seems to be a large debate on the tribe’s ancestry. Some say the Lumbee descend from Cheraw and related Siouan-speaking tribes; others members believe they descend from the Iroquion-speaking Tuscarora tribe. I decided not to pry any further, for I have a short historical attention span. Regardless, members of the Lumbee tribe continue to reside in this small town.

Maxton is located within Robeson County, the largest county in North Carolina (by size). About sixty-eight percent of the country is comprised of Native Americans with nearly 38 percent of this population belonging to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. I can recall my middle school days, sitting in a class comprise only of black and Native faces. It was in my social studies course at Townsend where I learned of the Battle of Maxton, commonly referred to as the Battle of Hayes Pond. My teacher, Mr. Brown, eloquently told the history of how the Lumbee Tribe ran the Klan out of Robeson County. Most of my classmates and I never heard of this historical event and honestly Mr. Brown was the only person who taught us this history. It is a history lesson, I will always teach.

The Ku Klux Klan is no stranger to North Carolina. During the 1950s, members would travel throughout the rural towns of North Carolina to intimidate Native Americans and blacks. This was mostly in part to public school desegregation. Robeson County was unique in the sense that there exist a tri-racial population of white, blacks, and Native Americans. Each race had their own separate, un-equal school system. In 1957, the Klan’s Grand Dragon, James W. “Catfish” Cole, an evangelist and radio preacher from South Carolina, built the Klan of southeastern North Carolina gaining nearly 15,000 allies. He led terror efforts against Lumbee Indians and other minority groups across the southeastern region of the state..

One of their documented harassments took place on January 13, 1958. A cross stood burning on the lawn of a Lumbee woman who was in a relationship with a white man. The Klan called this her warning. The Klan also burned a cross on the lawn of a Lumbee family that moved into a white neighborhood. Klan cars also cruised throughout the streets of Maxton, St. Paul, and Red Springs.

“They wanted you to see them. They wanted you to be afraid of them. And a lot of people were afraid.”

Cole called for a rally on January 18, 1958 near Maxton with two objectives:(1) to put the Natives in their places and (2) to end race mixing. The Lumbee Indians took note of his planned action and began to act.

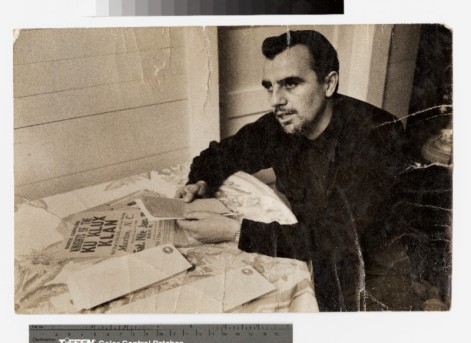

Originally the meeting was supposed to take place at a secure location, yet when it was rumor that local Lumbee members were to attend the location was changed to a secret location-a private field known as Hayes Pond, just outside of Maxton. The sheriff at the time traveled to South Carolina to encourage Cole to call and end to the rally for the Lumbees were not a group to cross. Cole failed to listen to the advice of the sheriff and proceeded with the event. To much of his surprise on the night of the rally less than 100 Klansmen arrived. Members brought a large “KKK” banner, a portable generator, one light, and a sound system. Before the event could even begin, members of the Lumbee tribe and former veterans Sanford Locklear, Simeon Oxendine, and Neill Lowery led an organized group of over 500 Lumbee men and women armed with guns and sticks. Due to the lack of light, they remained unseen as they surround the meeting. As they encircled the Klansmen and shot out their only light, the battle began and the Lumbee men and women (who stood nearby) defended their people against future Klan attacks. Cole and other members fled to a nearby swamp. To much to his embarrassment, Cole left his wife behind as well as the Klan’s banner, flyers, the unlit cross, and the sound system. Four Klansmen were slightly wounded.

“We would shoot our guns straight in the air. My shirt was full of my empty shotgun shells.”

Stanford Locklear

Lumbee members and onlookers celebrated by holding up the abandoned KKK banner and burning the remaining regalia while dancing around the open fire in native dances.

“I can assure you, I did a lot of dancing that night”

Garth Locklear,

The state’s governor at the time, Luther H. Hodges, denounced the Klan and their failed rally. Cole was later prosecuted and sentence for two years in jail. His crime—inciting a riot.

The Klan remained active across the state, but never held another meeting in Robeson County.

Links:

Battle of Hayes Pond: The Day Lumbees Ran the Klan Out of North Carolina

New Battle, Old Challenges: The Lumbee Indians at the Battle of Hayes Pond

The day the Klan messed with the wrong people

Lumbee tribe honors those who fought KKK in 1958, celebrates 50th anniversary

Leave a comment